In the year of its 40th anniversary, Ridley Scott’s masterpiece still knows how to caress the rawest topicality

by Fabrizio Ragonese

Predicting the future has always been one of mankind’s ancestral dreams, and paradoxically one of the most unsuccessful activities ever, with almost all attempts failing miserably, and this in direct proportion to the scope of the prediction: the more specific it was, the less accurate it was. Suffice it to say that, to give just one example, there were those who back in 1995 predicted the disappearance of the Internet within the following year…. But the law of large numbers means that, for every few wrong predictions, there is a right one. Tremendously right. Sometimes it comes via a statement, a book, an ancient manuscript, and sometimes….. via a film.

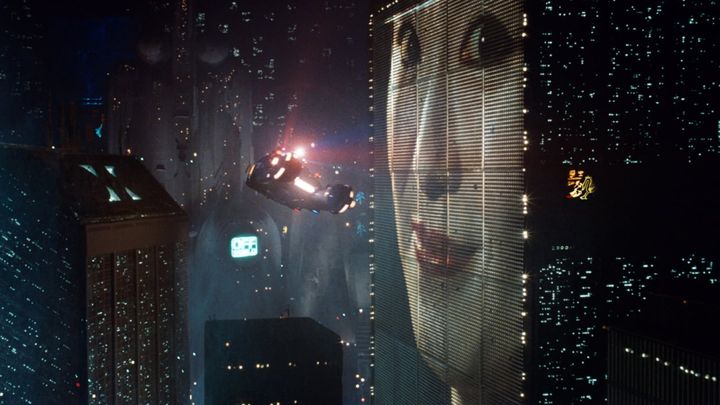

Forty years ago, in fact, Blade Runner was released, Ridley Scott’s masterpiece that still excites and nourishes a large number of fans; not only for the superb interpretations of the characters, for the post-futuristic atmospheres as disturbing as they are topical, and for the majestic soundtrack by Vangelis (never was a happier choice): no, the reason for its planetary success that still echoes today lies also and above all in the message, in the prophetic meaning contained in the film. Of this I will speak later. First I would say that it is worth spending a few words on the genesis of the film itself and its structure.

The film is loosely based on the 1968 novel The Android Hunter by Philip K. Dick, even though the two stories have significant differences. The first draft was written by actor Hampton Fancher, but turned out to be unwelcome to Dick, who considered it too different from his novel. Fancher then proposed his work to producer Michael Deeley, who instead found the proposal interesting and turned the draft over to Ridley Scott for a possible film adaptation. The latter, after some initial hesitation, accepted, but completely changed Fancher’s initial idea, giving it the noir-futuristic imprint that would characterise the entire film. This time the idea was enthusiastically welcomed by Dick, who however, paradoxically, never got to see the final version of the film, passing away shortly before its release.

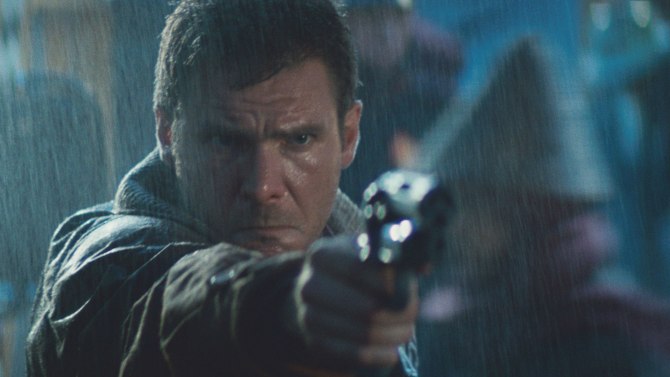

For the actors, too, there was the usual waltz of names before arriving at the final choice, especially with regard to the choice of the protagonist, Rick Deckard, for whom names such as Gene Hackman, Sean Connery and Jack Nicholson were initially hypothesised, but it was Harrison Ford who finally got the part, since he wanted a more dramatic role than the characters he had played up to then and immediately showed great interest in the project, which in the end, needless to say, turned out to be perfect for him. The cast was completed by actress Sean Young as Rachel, Edward James Olmos as Gaff, Joanna Cassidy as the android Zhora and Daryl Hannah as the android Pris. Finally, Joe Turkel appears in the role of Dr Eldon Tyrell, all of whom are very well cast.

And now, the film.

The main difference between the film and the novel lies in the different characterisation of humans and androids. While in the novel, in fact, the replicants are androids not only physically but also emotionally, in the sense that they are totally devoid of any emotionality, machines in the true sense of the word, in the film they are beings endowed with strong feelings (in particular Rachael, in the masterful performance of Sean Young), albeit immature, at times childish, but still feelings, particularly evident when they show all their frustration at the sad fate already written for them and their desperate desire to live, albeit with the knowledge that this is not life, as Gaff frankly admits in the finale. Those who, on the other hand, show all the calculating coldness typical of machines are paradoxically the humans themselves, who see the replicants as a problem to be solved, who do not sympathise in the least with their fears, and who generally show no trace of the humanity that should belong to them.

The most controversial part is undoubtedly the ending, which changes depending on the version (as many as seven different ones will be released): the original version was negatively received by the public, which led to initial changes, which gave rise to the so-called Domestic Cut, conceived for the American market and containing important additions, including the voice-over and a happy ending with Rachael and Deckard’s elopement; the version launched for the European market, called the International Cut, contained some scenes cut from the American version. The Director’s Cut, which is much closer to the film originally conceived by Ridley Scott and supervised by Michael Arick, does not feature Deckard’s voice-over nor the happy ending included in previous versions. Always absent, however, are the violent scenes present in the International Cut. This version also contains a crucial moment: Deckard’s dream. In this version, in fact, Deckard dreams of a unicorn galloping through a forest, and in the film’s finale, Deckard himself finds in his flat an origami in the shape of a unicorn, left there by Gaff to indicate that he has already been there and is hunting down Rachael, which suggests that the agent is aware of his elopement with her and above all that the dream is nothing more than an artificial graft, just like Rachael’s memories, and that Deckard is therefore in fact a replicant. Scott himself later confirmed that he wanted to give precisely this impression, in stark contrast to the wishes of Ford, who instead always rejected this possibility (it is said that he even came to blows with the director over this), feeling that the audience needed a character for whom they could take sides.

In short, it was suggested, but not specifically stated. The heavens opened: since then, 25 years of heated and uninterrupted debates among fans on one and the same question: is Deckard a replicant or not? The definitive answer seems to have been given by the sequel, which is very successful despite the many years of distance, showing a Harrison Ford in the part of a tired, embittered, and ageing ex-cop, which definitively rules out the possibility that Deckard was a replicant, since replicants do not age, having only 4 years of life.

I said earlier that the secret of the film’s success lies in its prophetic significance, well ahead of its time. The replicants, who in theory are supposed to be androids who do not even know what feelings are, are actually ‘more human than humans’, as Tyrell puts it, because they display a fair range of feelings, albeit immature and immature, that those who should have them by nature, that is, humans themselves, lack. Even the brutal Roy Batty, after beating Deckard, saves his life anyway, showing an unexpected human side. And so the first question arises: what does it really mean to be human? Who is really human and who is not? Is it possible that mankind, in a hyper-technological world, is somehow losing its humanity? It sounds like a question asked on a talk show today, but it is actually a 40-year-old question.

It is the same question that sociologists ask themselves now, seeing the hordes of millennials completely depersonalised by smartphones, seeing relationships cooled by digitalisation, yet there were those who were already asking it then. The second question is even more topical than the first, because it calls into question artificial intelligence, a science-fiction notion in the world of 1982, and which has now entered our lives in a big way. How far can artificial intelligence go? Could machines one day be so sophisticated as to be indistinguishable from human beings? Could they come to take over from humans? All these burning ethical questions, which were entirely hypothetical at the time, are the same ones we now face every day. Unbelievable. With Blade Runner, Ridley Scott really did see the future, just as the unforgettable Rutger Hauer did in his final monologue (largely improvised, just to understand the character’s calibre): ‘I have seen things you humans could not imagine…’. How can you blame him?

Mediafrequenza Attualità, cultura, sport, spettacolo

Mediafrequenza Attualità, cultura, sport, spettacolo